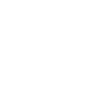

Our sequoia forest fire diagram shows the levels of fire severity in a sequoia grove. 1.) An overgrown forest with dense underbrush may look pretty, but it is primed for high-intensity California wildfires. 2) A prescribed burn removes excessive undergrowth, helping to reduce fire severity. 3) 10 years ago, our severe forest fire definition used to include surviving sequoia trees, but today. 4) fires have become so severe that only matchsticks tree trunks remain.

Visualizing the Changing Wildfire Severity and Impact

Devastation. Each year, it feels like more and more wildfires leave us with no other word to describe them—from Australia’s Black Summer of 2019-2020, to the California Camp fire in 2021, to 2023’s destruction of Lahaina, Maui and the fires across Canada—devastation. Wildfire likelihood and severity continue to rise with increasing global temperatures. As heatwaves and droughts worsen, wildfires leave more communities vulnerable to infrastructure damage, smoke exposure, and loss of life.

The World Resources Institute has an excellent summary of worsening global forest fires, while scientists recently published a paper on increasing wildfire risk in California. California’s National Parks, particularly Yosemite and Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks, have over a century of experience with wildfires. Their boots-on-the-ground experience has seen fire severity increase so much since 2015, that they’ve had to change their fire severity definition. In this post, we look at our Sequoia forest fire diagram series, illustrating:

- The changing severity of forest fires in sequoia groves

- The hope that these fires’ devastation may be lessened with changing land management.

Drawing Guidance from Forest Fires in Sequoia Groves

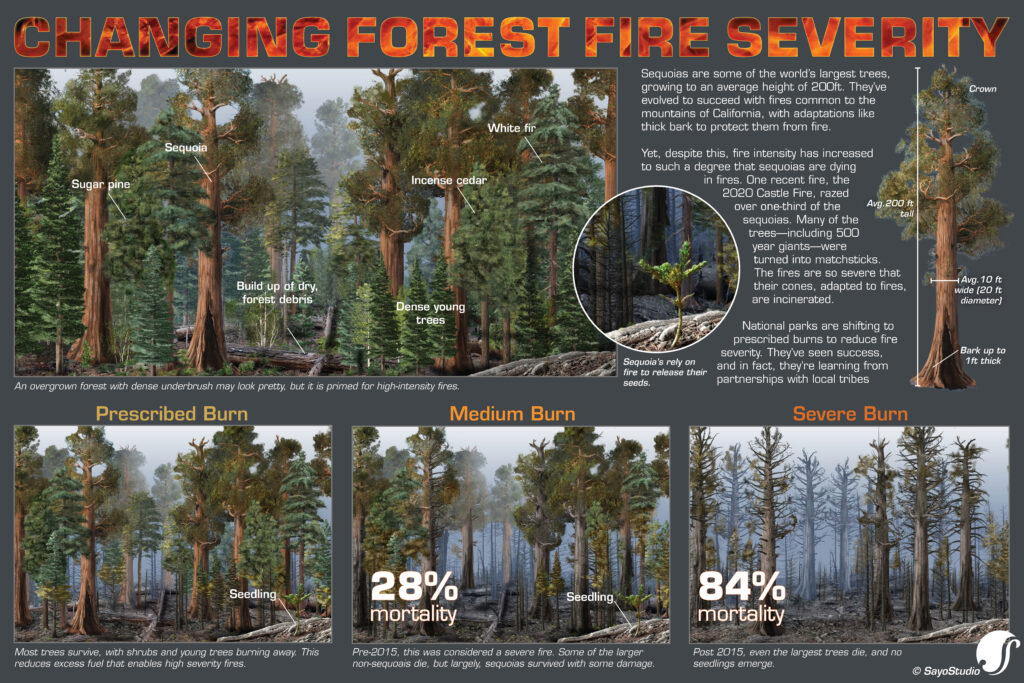

First, we need to introduce you to sequoias, and what makes them so special. Sequoias, endemic to California, are some of the world’s largest trees. They reach upwards of 200 feet tall and over 20 feet in diameter. And perhaps most impressively, they live over 3,000 years. To do so, they have evolved to survive and succeed in the mountainous areas where lightning is frequent. Some of sequoias adaptations to fire include:

-

- Thick bark to protect the lower part of their trunks from fire (up to one foot!)

- Cones that rely on fire’s heat to release their seeds

- Seedlings use the ashy nutrient-rich left behind by fires

Yet, despite these adaptations, fire intensity has increased to such a degree that sequoias are dying in fires. One recent fire, the 2020 Castle Fire, razed over 30% of the sequoias in an entire grove. Some of the trees—including giants over 3,000 years old—were turned into matchsticks. These recent fires are so severe that their cones, despite fire adaptations, are incinerated.

To illustrate this harsh reality, we worked with Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks to create a new fire severity diagram.

Illustrating A Changing Wildfire Index- Forest Fire Diagram

Wildfires thrive on undergrowth and understory trees. With smaller trees like sugar pines and firs growing too close to sequoias, the heat increases, and sparks jump to the branches of the sequoias—burning their way into their upper canopy. The sequoias’ thick bark- which traditionally protected them from fires, is no match with tinder growing up against it.

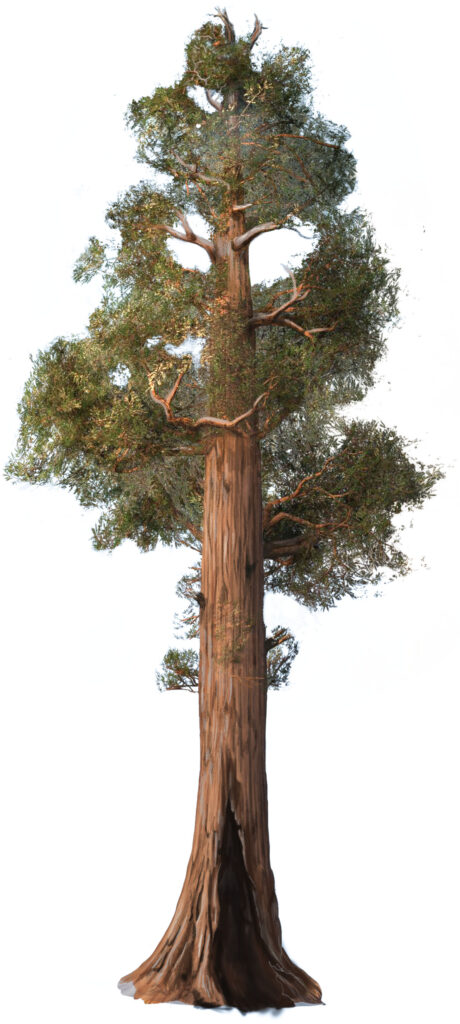

Land managers and ecologists have had to change their definitions of severe fires. What used to be a high-severity fire is now only considered a moderate-fire. The question remains, will sequoias survive?

Prior to 2015 severe fires left surviving sequoias and sequoia cones ready to grow. Post-2015, we’ve had to change our definition of severe. Now, the worst fires kill 84% of the sequoias, and incinerate any cones. Forest fire diagram illustration created by Nicolle Fuller and May Jernigan, SayoStudio

Navigating the Flames: What Can We Do to Save Sequoias?

What can we do? As climate change persists, the answer seems bleak. Rising temperatures contribute to dry conditions and reduced precipitation, desiccating vegetation and turning it into fuel for fires. Even in the tropical landscape of Lahaina, initial reports point to overgrown non-native grasses and bushes fueling the inferno. The good news is, is that this leads us to one answer on how we can reduce fire severity: reduce overgrown undergrowth and debris.

But how can fuel for fires be reduced, in an ecologically responsible manner?

Fighting Fire with Fire (Literally): The Future of Forest Fire Ecology

Centuries ago, small-scale fires were frequent, reducing the extra brush that now fuels large fires. In fact, in the not-so-distant past native tribes like the Karuk and the Yurok people of northern California limited fire intensity with curltural burns. Western settlers displaced native tribes, while the U.S. federal government’s encroaching policies outlawed native people’s cultural practices, and any and all prescribed burning was outlawed.

The difference is stark; decades of fire suppression (often well-meaning) has led to lands full to the brim of burnable tinder. Now, U.S. federal agencies like the Forest Service are forging partnerships with local tribes to learn from their centuries of controlled burns. Ecologists and agencies like the National Parks have shown that these ancient practices work to reduce fire severity.

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Park have had success using prescribed burns to reduce fire severity. Evidence-backed prescribed burns are one way to help protect sequoia groves, as well as ecosystems and their neighboring communities far beyond.

Wildfire Resources

In addition to links throughout the article, here are some great resources to learn more:

- U.S. National Parks Sequoia Prescribed Burns plan

- Journal Article: Ancient trees and modern wildfires: Declining resilience to wildfire in the highly fire-adapted giant sequoia

- USDA fire season change to all year